If I could use one word to describe the advancement of ML or AI in the past couple of years it would be scale. When GPT-31 was released in 2020 and ChatGPT2 in 2022, I was impressed with the performance and thought it was essentially a step towards generalisation in Natural Language Processing (NLP), similar to how AlexNet3 allowed for generalization in image classification. I did not fully grasp the significance Large Language Models (LLMs) would have on robotics and ML in general. The main idea, that I missed, is the significance and relationship of NLP to problems humans have, language is a very expressive format and a key discovery we made by scaling up these LLMs is that by training over internet scale data we have in fact built a very large and expressive model of human sentiment. Sergey Levine recently described this as:

A behavioral model of what humans tend to do with a computer, keyboard, and mouse.

Following the explosion of LLMs, labs with the resources to do so, have begun to develop large scale models for robotics. These scaled-up robotic models have become known as foundation models, serving as the base upon which entire robotic platforms are built. I prefer this term over large since what constitutes large today often becomes small tomorrow. Figure 1 shows the number of parameters each model has against time, though I couldn’t find a suitable benchmark for comparison, an issue I will come to later on. Unlike in the LLM space, there isn’t a clear bigger is better trend emerging in robotics. Whilst I suspect the recently released Gemini Robotics VLA4 could be very large given the trend from RT-2 the model specifics are not included in the paper. The bigger is better trend hasn’t proven true for robotic foundation models, at least not yet. In this article I aim to explore:

- How foundation models work: The architectural principles behind robotic foundation models, including how they integrate multi-modal data (vision, language, motor control) and differ from pure language models in their design and training approaches.

- Applications and data collection: Real-world use cases where these models are being deployed, the types of robotics data being collected to train them, and how this data differs from the internet-scale text that powers LLMs.

- Current problems and emerging solutions: The key limitations facing robotic foundation models today (scaling challenges, benchmarking gaps, deployment issues) and the research directions and technical approaches being developed to address them.

Foundation Models

To understand how foundation models work, let’s first briefly examine how LLMs work, as these form the basis of how foundation models are applied across different domains. Modern LLM development follows a two-stage process: pre-training and post-training. Pre-training involves training the core LLM architecture on large datasets to learn language patterns and world knowledge. Post-training5 then fine-tunes the model through techniques like Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) and Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) to improve alignment and task-specific capabilities.

The general objective function of an LLM during pre-training can be thought of as:

Given a sequence of words, predict the most likely next word.

This process involves 3 key components/processes:

- Embedding, converts text into a tokenized vector representation. Tokenization first breaks text into subword units (tokens), which are then mapped to learned vector embeddings which capture the semantic meaning in high-dimensional space.

- Transformers, are the main building blocks of the LLM architecture. Each transformer contains an attention mechanism that allows tokens to selectively focus on and communicate with other relevant tokens in the sequence. Typically, a Multi Layer Perceptron (MLP) further refines each token’s representation. Multiple transformer layers are stacked on top of each other to build deep networks.

- Output Probabilities, the final linear and softmax layers transform the processed embeddings into a probability distribution over the entire vocabulary, determining which token is most likely to come next.

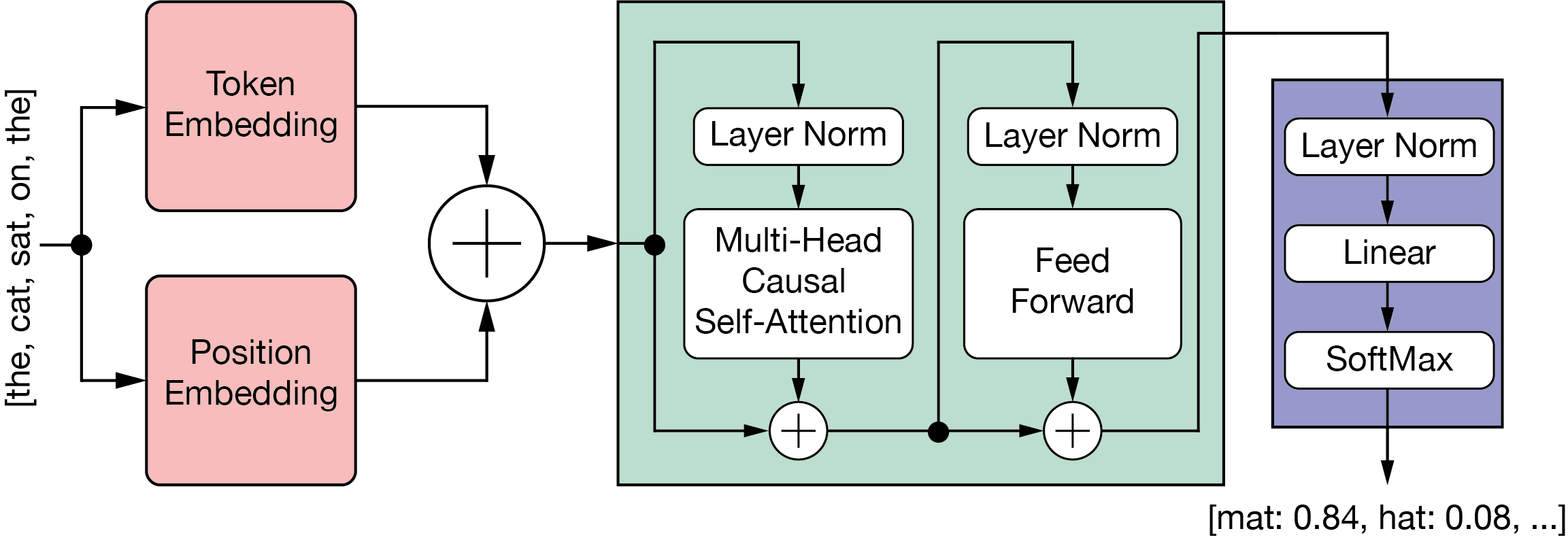

Several excellent resources help explain how transformers and LLMs work. I particularly recommend this visualisation. Figure 2 shows the general structure of LLMs as a block architecture.

Figure 2: LLM Block architecture.

For language models and foundation models in general, it is best to think of everything as vectors. This vector representation allows mathematical operations and enables models to process and manipulate semantic information numerically. The input can be represented as a vector:

$$ \mathbf{x} = (x_{0}, x_{1}, x_{2}, \ldots, x_{n}). $$The prevailing approach to large scale modelling are autoregressive where the output is represented as:

$$ P(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x}) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(y_{i} | \mathbf{x}, y_{1:i-1}). $$This equation represents the chain rule of probability, where $y_{1:i-1}$ denotes all previous tokens up to position $i-1$. In practical terms, this autoregressive approach means that LLMs generate text one token at a time, with each new token conditioned on both the original input and all previously generated tokens.

General Foundation Models

While LLMs exclusively process text tokens, the same transformer architecture and training methodology can be adapted to handle other types of sequential data including:

- Images, are divided into patches and treated as visual tokens. For example CLIP6 learns joint image-text representations through contrastive training on (image, text) pairs.

- Audio spectrograms, are tokenized as spectogram patches for audio classification7.

- Time series, data is segmented into windows for forecasting8 and anomaly detection9.

- Action sequences, can be tokenised for RL. Decision Transformer10 eliminates value functions entirely by framing RL as a conditional sequence modelling problem.

- Multimodal inputs, combine multiple token types. Flamingo11, is an early example of interleaving vision-language sequences. Most modern frontier labs offer multimodal versions of their large-language models. Modern multi-modal examples/foundation models include Meta’s Llama12, X.AIs Grok-1.5v, Anthropic’s Claude, OpenAI’s GPT4o13 and Google/DeepMind’s Gemini14. These can handle text, images, audio and video.

Robotic Foundation Models

Foundation models for robotics face a fundamentally different challenge than pure language models, the need to interact with the physical world. While LLMs predict the next token in a text sequence, robotic foundation models must predict actions that will be executed by physical systems in the real world. This shift from virtual to physical introduces several key differences. Robotic foundation models need to:

- Understand the embodiment constraints of the robot, meaning the model must comprehend the robots physical limitations, spatial relationships and potential outcomes.

- The model must also run in real-time creating lower latency demands for safe operation.

- Multimodal integration is essential as robots need to process vision, proprioception, language instructions and other sensor inputs simultaneously.

The most successful robotic foundation models follow the Vision-Language-Action (VLA) paradigm, which extends the transformer architecture to handle three key modalities:

- Vision, processes camera feeds and depth sensors tokenised as image patches.

- Language, handles natural language instructions and task descriptions.

- Action, converts robot joint commands and end-effector movements into discrete tokens.

RT-115 (Robot Transformer) was the first robotic foundation model, developed by Google Robotics and Everyday Robotics in 2022. The system was trained on approximately 130,000 robot demonstrations collected over 17 months using a fleet of 13 robots, covering over 700 distinct tasks across multiple kitchen-based environments. RT-1 was trained and deployed on Everyday Robots mobile manipulator robots, a 7 degree of freedom robot with a 2 finger gripper and mobile base shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Everyday Robot platform.

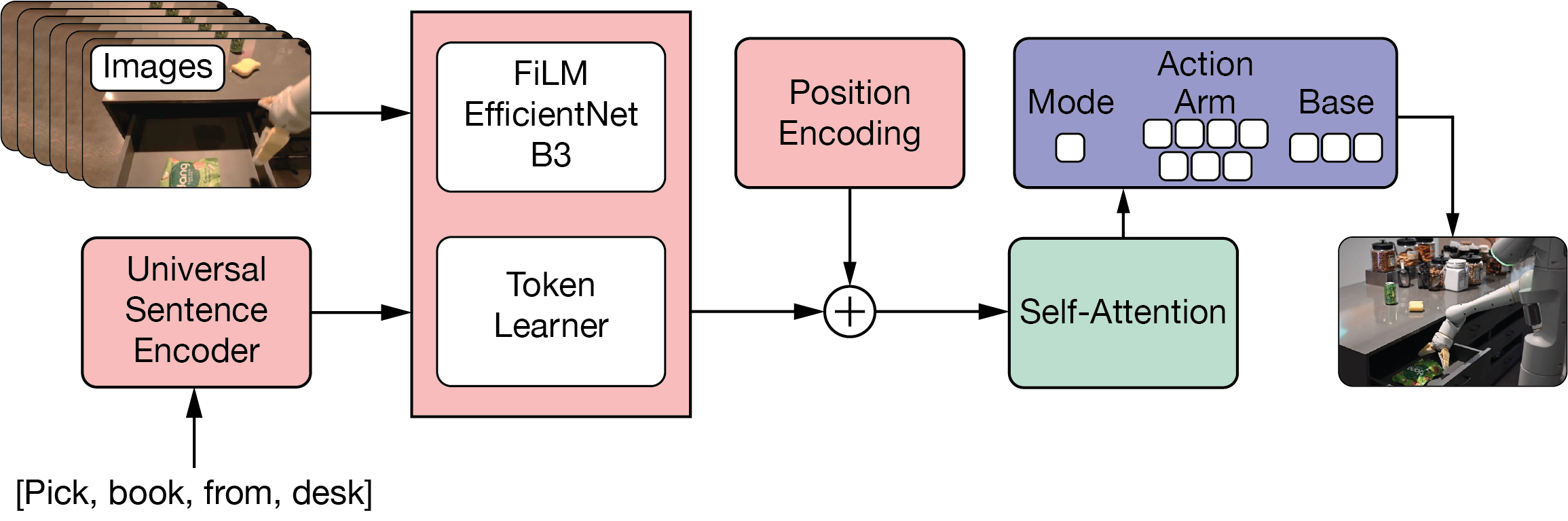

RT-1’s architecture is designed for both high performance and real-time operation. The system takes natural language instructions and images from 6 cameras as input, processing them through a FiLM-conditioned EfficientNet-B316 that combines language and vision information early in the pipeline. The resulting 81 tokens are compressed to just 8 tokens using TokenLearner17, which retains only the most important information. These compressed tokens feed into a Transformer with 8 attention layers that outputs discrete action commands across 11 dimensions: 7 for arm movement, 3 for base movement, and 1 for mode selection, with each dimension divided into 256 possible values. Despite having 35 million parameters, this design runs at 3 Hz for real-time robot control.

Figure 4: RT1 Architecture.

Advancing VLAs

Over the past several years LLM developers have leveraged massive datasets scraped from the internet to rapidly develop their model capabilities. Robotics doesn’t have this luxury. Unlike text, which exists abundantly online, robotic learning requires physical interaction data: demonstrations of robots manipulating objects, navigating environments, and performing tasks in the real world. This embodied data is expensive to collect, difficult to standardize across different robotic platforms, and challenging to scale. As a result, robotics lacks the massive, unified datasets that have powered breakthroughs in NLP, creating a significant bottleneck for developing capable robot foundation models.

This has pushed robotics labs to develop several novel approaches towards data collection and model design. Collaborative data collection across different laboratories and robot types is one promising direction, though the largest dataset currently available, the Open-X Embodiment Dataset18 is still relatively limited. Out of 73 datasets, 55 focus on single-arm manipulation with tabletop setups using toy kitchen objects, and data collection still predominantly relies on human experts using VR or haptic devices. Companies like Covariant have found success combining real-world data with synthetic data, while others are exploring reinforcement learning in production environments.

Evaluating progress across these diverse approaches remains challenging since current VLA models show significant variation in performance across different tasks and robot platforms, and there’s no standardized robotic setup. However, several key metrics have emerged that are useful for practitioners and have generally shown improvement across VLA development:

- Inference Speed measures how quickly the model can generate actions. Unlike LLMs where users can tolerate multi-second response times, robots require real-time control, modern VLAs achieve anywhere from 6Hz (OpenVLA) to 120Hz (GR00T N1’s fast system).

- Memory Requirements determine the hardware needed for deployment. VLAs face unique constraints compared to LLMs since they often must run on-device or locally to minimize response latency. Recent advances in quantization and architecture design have reduced model memory footprints significantly.

- Training Efficiency encompasses both initial training time and fine-tuning speed for new tasks or robot platforms. Since the deployment platform often differs from the training environment, efficient adaptation becomes crucial. Modern approaches like LoRA fine-tuning can reduce training time by 70%, while some models now require as few as 50 demonstration episodes to learn new behaviors.

Beyond these quantifiable metrics, VLAs have improved in areas that are more challenging to measure directly, such as zero-shot generalization to novel objects, cross-task transfer capabilities, and overall success rates across diverse manipulation scenarios. These improvements reflect the field’s progression from narrow, task-specific policies to generalizable robotic foundation models.

Early VLAs

RT-219 extended RT-1 and coined the term VLA. By adapting pre-trained VLMs, using either PaLI-X20 (55B) or PaLM-E21 (562B) as base architectures. Rather than training robotic policies from scratch, RT-2 finetunes these VLMs on a mixture of web data and robot trajectories, maintaining the original language capabilities while learning robotic control. The main innovation is in representing robot actions as natural language tokens (e.g. [2, 64, 30, 1, 0, 1, 0], for discrete arm and gripper commands), allowing the same transformer architecture to generate both text and robot actions. During robotic tasks, RT-2 constrains its vocabulary to valid action tokens through dynamic vocabulary masking. This approach allowed for compositional reasoning, RT-2 can follow abstract instructions like “place the apple next to the coffee mug” or “move the block onto the number that equals 3*2”.

Figure 5: RT-2 pushing the blue block to the tabasco bottle.

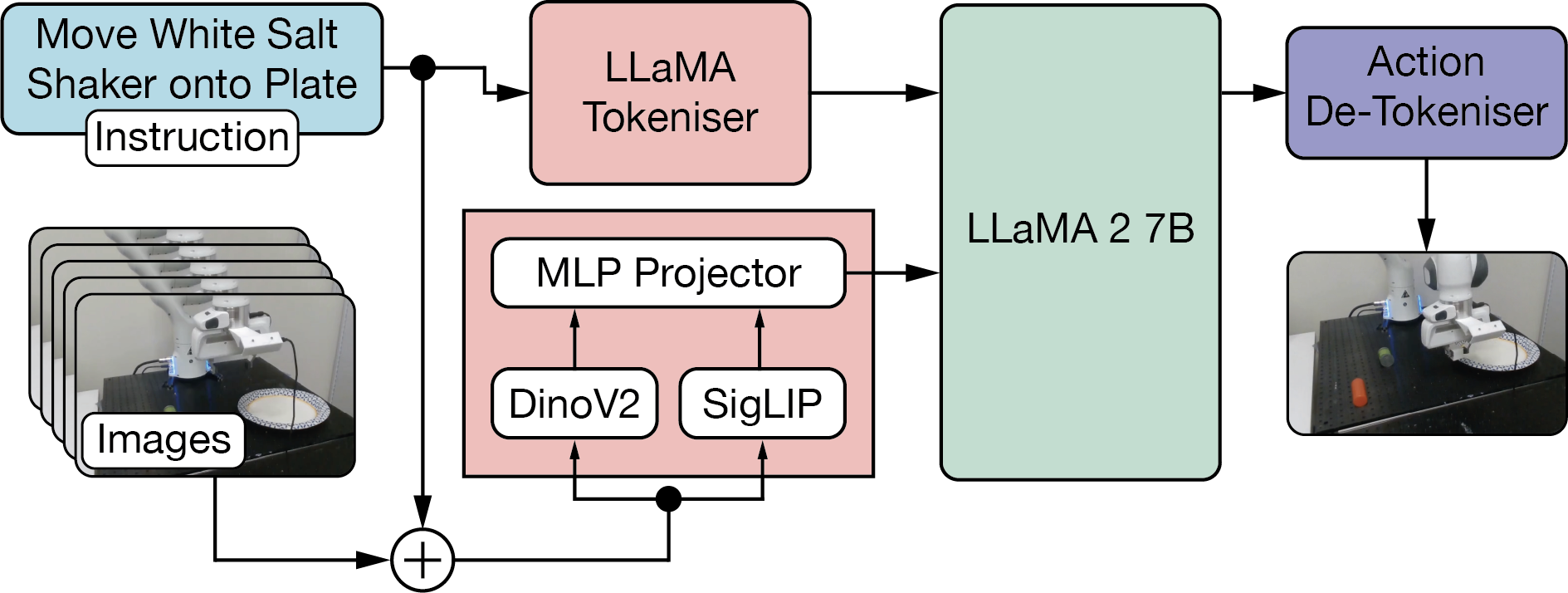

OpenVLA22 achieved better performance than RT-2’s 55B parameter model using only 7B parameters. The model uses a Prismatic-7B vision-language foundation23 based on LLama224 with a fused visual encoder. This encoder combines SigLIP25 (contrastive text-image embeddings similar to CLIP) and DINOv226 (a visual foundation model for patch and class token embeddings) projecting them into LLaMA-2’s token space for action prediction. OpenVLA’s main innovation is a more efficient action tokenization scheme. While RT-2 represents actions as strings like “move_arm(x=0.5, y=0.3, z=0.2, gripper=open)”, OpenVLA directly tokenizes continuous action values as numerical tokens: [0.5, 0.3, 0.2, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0] corresponding to 3D position, quaternion rotation, and gripper state. This reduces vocabulary overhead and improves training stability. OpenVLA was trained on 970k robot trajectories from the Open X-Embodiment dataset18 spanning 22 different robot embodiments. The model can be fine-tuned using LoRA27 techniques for new tasks and achieves 16.5% better task success rates than RT-2-X across 29 evaluation tasks while running at 6Hz inference speed.

Figure 6: OpenVLA Architecture.

Continuous VLAs

All models discussed so far are discrete. The output actions sent to the robot are quantized, typically into 256 bins per action dimension 28. While this quantization makes it easier to debug and validate model outputs, it creates challenges for fine-grained control and smooth motion generation. In contrast, continuous VLAs generate raw motor commands or joint positions directly from visual and language inputs without quantization.

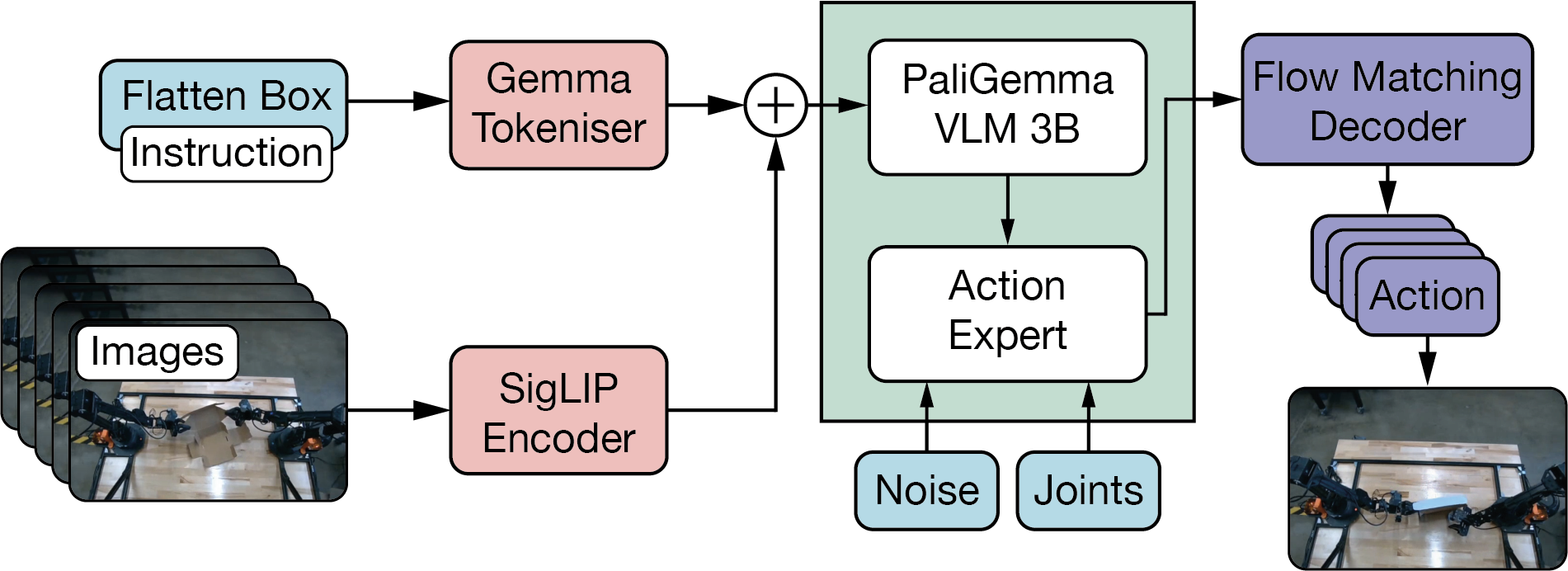

Physical Intelligence’s $\pi_{0}$29 model exemplifies this approach, using flow matching30 to generate 50Hz continuous control signals for dexterous manipulation tasks. Flow matching is a diffusion-inspired generative modeling technique that learns to transform Gaussian noise into structured action trajectories. Unlike diffusion models which require multiple denoising steps, flow matching enables real-time control by directly generating smooth action sequences. $\pi_{0}$ uses a hybrid architecture with a 3B parameter VLM based on PaliGemma31 for vision-language processing, and a separate 300 million parameter action expert that handles proprioceptive states and generates continuous actions via flow matching. The model was trained on over 10,000 hours of robot data from 7 different robot platforms across 68 distinct tasks, enabling it to perform complex dexterous manipulation like folding laundry, table bussing, and precise object handling that require the fine motor control impossible with discrete action spaces.

Figure 7: $\pi_{0}$ Architecture.

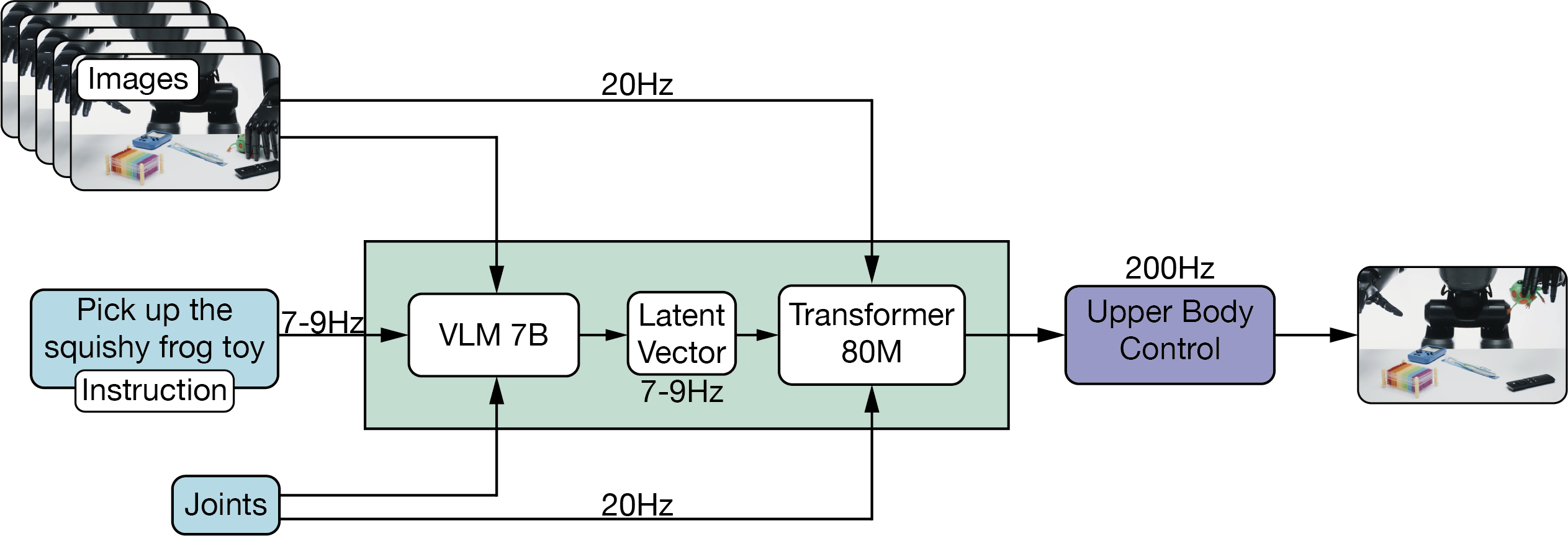

Figure AI’s Helix model uses a dual-system architecture to address the tradeoff between generalisation and speed in VLA models. System 2 (S2) is a 7B parameter VLM operating at 7-9 Hz for scene understanding and language comprehension, while System (S1) is an 80M parameter cross-attention encoder-decoder transformer that handles low-level control at 200Hz. This seperation allows each system to operate at its optimal timescale. S2 can think slow about high-level goals, while S1 thinks fast to execute precise actions. S2’s latent vector is projected onto S1’s token space and concatenated with visual features from S1’s vision backbone along the sequence dimension, providing task conditioning. This latent vector is a semantic embedding that encodes S2’s understanding of the scene and language instruction for S1’s motor control. S1 outputs continuous control signals including wrist poses, finger flexion, and abduction control at 200Hz. Helix was trained on approximately 500 hours of teleoperated behaviours and can simultaneously control 2 robots working on shared manipulation tasks. Unfortunately, Figure AI is closed source and outside their blog post there is not a huge amount more information available.

Figure 8: Helix Dual System Architecture.

Efficient VLAs

While models like RT-2 and $\pi_{0}$ demonstrate impressive capabilities, their computational requirements limit practical deployment. A parallel research direction focuses on efficiency optimization—achieving good performance with fewer parameters and less compute.

- CogACT32 breaks from the monolithic VLM approach used in RT-2 and OpenVLA by separating cognitive and action capabilities into distinct modules. Unlike previous VLAs that adapt vision-language models end-to-end, CogACT uses a dedicated 300M parameter Diffusion Transformer specifically for action modeling, while keeping the Prismatic-7B VLM focused purely on vision-language understanding. This separation allows independent optimization of each component and enables the action module to specialize in temporal action sequences.

- TinyVLA33 eliminates the pre-training stage entirely—a departure from the standard VLM robot fine-tuning pipeline. Instead of starting with large pre-trained VLMs like RT-2 or OpenVLA, TinyVLA directly integrates diffusion policy decoders during fine-tuning on robot data, significantly reducing training costs while maintaining performance.

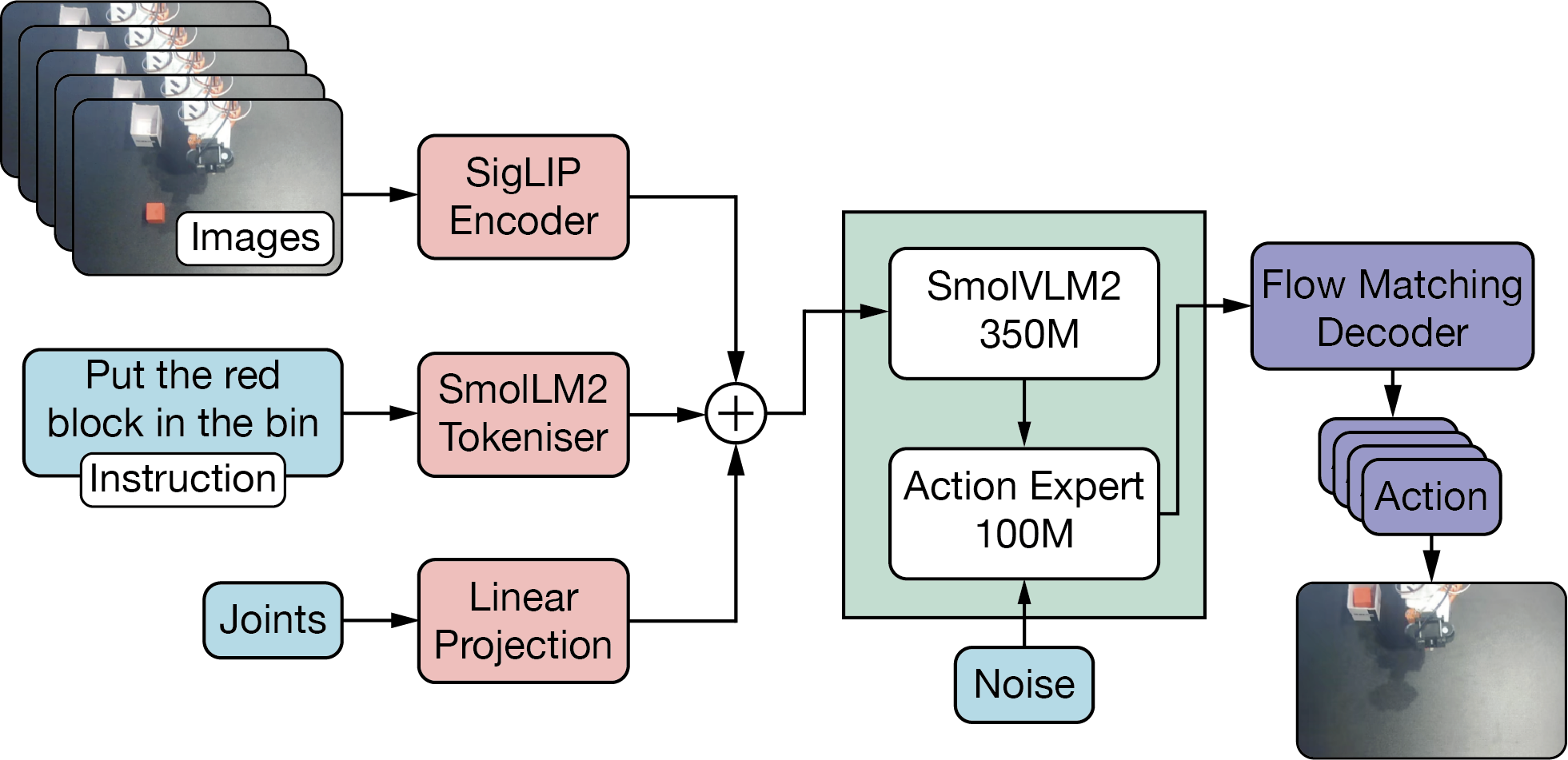

- SmolVLA34 represents the extreme end of parameter efficiency, using a 450M parameter model with SmolVLM2 as its backbone and a 100M parameter action expert. Designed for consumer-grade hardware, SmolVLA demonstrates that effective robotic control doesn’t require massive models. The model was trained exclusively on community-contributed datasets, showing how smaller models can leverage diverse data sources that might be insufficient for larger architectures.

Figure 9: SmolVLA Architecture.

Limitations and Open Problems

Despite remarkable progress, VLA models still face fundamental challenges that constrain deployment beyond controlled laboratory settings. Understanding these limitations is crucial for building reliable robotic systems that can operate safely in the real world.

Data Bottleneck

VLA models suffer from a fundamental data scarcity problem that makes their development different from their language model counterparts. While GPT-style models train on billions of text examples scraped from the internet, even the largest robotic datasets remain tiny by comparison. OpenVLA, one of the most trained VLAs, used approximately 970,000 trajectories from the Open X-Embodiment dataset using 22 robot platforms, still orders of magnitude smaller than typical language model training sets.

This scarcity stems from the inherent economics of robotic data collection. Unlike text, which exists abundantly online, robotic learning requires physical interaction data that must be generated through expensive human tele-operation or autonomous exploration. Physical Intelligence estimates robotic data collection costs approximately 50 - 100 dollars per hour, compared to pennies for text data. The RT-1 dataset required 17 months of continuous data collection using a fleet of 13 robots to gather 130,000 demonstrations across 700 tasks, a massive undertaking that produced what would be considered a small dataset in the language modeling world. Larger datasets are beginning to emerge however, AgiBot Colloseo35 passes just over one million and invests serious infrastructure to access the datasets.

The computational scaling challenges compound this problem. For example, RT-2’s 55B parameter model required 64 NVIDIA A100 GPUs running for 15 days to fully train. This would cost approximately $60,000 on most commercial clouds, too much for most university’s departments research budgets! This carries over to deployment as well. Unlike language models that can leverage cloud-based inference, real-time robotic control demands low-latency responses that often necessitate running models locally, introducing additional hardware constraints.

Recent advances in synthetic data generation offer promising but incomplete solutions. NVIDIA’s Isaac GR00T Blueprint36 can generate 780,000 synthetic trajectories in 11 hours, equivalent to 6,500 hours of human demonstration data. However, sim-to-real transfer typically sees 50-80% performance drops when moving from simulation to physical hardware. The challenge lies not just in generating realistic physics simulation, but in capturing the subtle environmental variations and edge cases that robots encounter in real-world deployment.

Figure 10: Isaac GR00T-N1.5-3B in action.

One exciting but underexplored idea is the robotics research cloud37, shared facilities with fleets of standardized robots accessible remotely over the internet. Instead of every lab investing hundreds of thousands of dollars on robots that often sit idle between experiments, researchers could pool resources and share access. Teams could upload their VLA policies, run evaluations across diverse manipulation tasks, and collect trajectory data for future training iterations—all without maintaining their own physical labs. Small-scale versions exist Georgia Tech’s Robotarium38, Real Robot Challenge39, but scaling this to manipulation tasks could provide the standardized infrastructure that VLA development needs. This approach could democratise access to robotics by offering robotic training as a service, similar to how cloud providers simplify infrastructure for software development. Helping address what is becoming a growing problem of scale.

Safety and Reliability in Physical Systems

The transition from laboratory demonstrations to real-world deployment exposes critical safety limitations that don’t exist in purely digital AI systems. When language models hallucinate, the consequence is typically an incorrect text output. When VLA models hallucinate, robots can perform dangerous actions including collision failures, incorrect force application, or unsafe trajectories that could cause physical damage or human injury.

VLATest40 recently evaluated several VLAs across 18,604 testing scenes and showed that models often exhibit significant performance degradation under relatively minor environmental changes. Success rates drop dramatically with variations in lighting conditions, camera angles, or obstacle configuration. Models also frequently misidentify target objects when distractors are present, leading to task failures that could be a direct safety risk in production environments.

The reliability challenges extend beyond environmental sensitivity to fundamental issues with uncertainty quantification and failure detection41. Current VLA models lack robust mechanisms for recognizing when they are operating outside their training distribution or when their confidence in a particular action sequence is low. Unlike the controlled environments often showcased in VLA papers, real-world deployment introduces countless edge cases and environmental variations that weren’t captured in training data.

Recent commercial deployments highlight both progress and persistent limitations. Physical Intelligence’s $\pi_{0.5}$ model42 operates successfully in rental homes in San Francisco, showing progress of open-world generalisation beyond laboratory settings. Figure AI has certified and deployed their robots in BMWs manufacturing operations.

The threat of bad actors is also a concern and research is emerging into VLA adversarial attacks43. VLA models remain susceptible to patch-based attacks44 in both digital and physical settings, where carefully crafted visual perturbations can induce path deviations and disrupt spatial perception. While such attacks might seem academic, they reveal fundamental brittleness in the models’ visual processing that could be triggered by natural environmental features or wear patterns on equipment.

Generalisation and Transfer Learning

VLAs represent a significant step toward general-purpose robotic intelligence, yet their deployment beyond controlled laboratory settings reveals fundamental limitations in generalisation and transfer learning. Understanding these challenges, and the emerging solutions to address them, is key to the field’s progression toward general robotic systems.

Modern VLAs perform poorly when confronted with scenarios outside their training distribution. OpenVLA completely fails on unseen environments without fine-tuning on each new deployment scenarios. This is a significant problem when considering the diversity of real world environments where robots are expected to operate.

Several promising solutions are emerging to address this challenge. RT-2 demonstrates improved generalisation primarily through exposure to large-scale internet data during training, which provides broader world knowledge. However, the recently released $\pi_{0.5}$42 model from Physical Intelligence represents more significant progress towards this goal. It achieved the first demonstration of a robot successfully performing complex household tasks in completely unseen homes without any additional training. $\pi_{0.5}$ accomplishes this through two main innovations:

- Heterogeneous co-training: Rather than training solely on target robot data, $\pi_{0.5}$ learns from a diverse mixture including mobile robot demonstrations across 100+ homes, data from other robot types, high-level semantic prediction tasks, web-scale vision-language data, and verbal instructions from human supervisors. This varied training regime helps the model develop more robust and transferable representations.

- A hierarchical reasoning system: Similar to Chain-of-Thought (CoT)45 in LLMs, $\pi_{0.5}$ first predicts high-level semantic subtasks before generating low-level motor commands. This separation allows the model to leverage different types of knowledge at each level, semantic understanding from web data for high level planning, and precise motor skills from robot demonstrations for execution.

Figure 11: $\pi_{0.5}$ kitchen tasks in a new kitchen.

I strongly recommend reading the $\pi_{0.5}$42 paper as it contains some fascinating details about their specific implementations and evaluations.

Similar challenges initially plagued cross-embodiment generalisation, where models struggled to transfer skills across different robot bodies. However, recent advancements, particularly with RT-2-X and $\pi_{0}$, have begun to bridge this gap. These models have shown improved generalisation by primarily scaling up the diversity and volume of training data, allowing them to learn more robust and transferable representations that are less tied to a specific robot’s physical form.

Evaluation for VLAs is still relatively limited compared to LLMs, which is also an area that is lagging. In general VLAs autoregressive nature makes them relatively myopic, they optimise for the immediate next action rather than planning entire sequences. This means they often struggle with more complex reasoning tasks and long-horizon planning. VLABench46, a VLA manipulation simulation evaluation environment, found that over 100 task categories VLAs exhibit a 20% success rate on tasks that required complex reasoning or planning. These results were not compared against $\pi_{0.5}$ which may have made progress if compared against these.

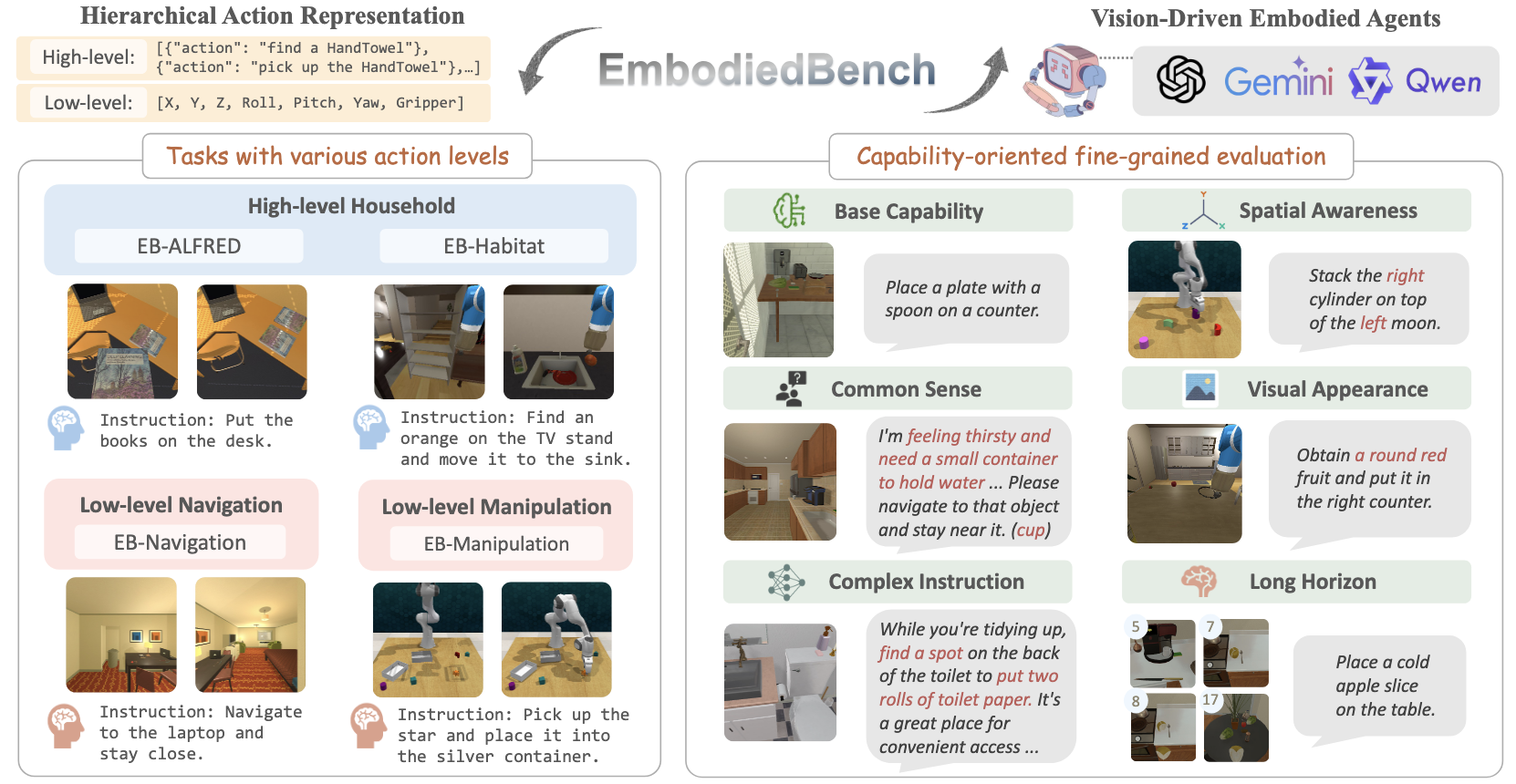

There is still no unified evaluation benchmark for VLA evaluation. VLABench and CALVIN47 are good synthetic benchmarks for general purpose robotic manipulation, and the recently released EmbodiedBench48 looks to offer an exciting range of evaluation tasks. Fundamentally none of these benchmarks are standardised on real robots. Ideally we need a way to evaluate robots performance in the real world on a series of tasks. I suspect we may see something similar to a robot skill test emerging in the next couple of years to evaluate models and validate skills.

Figure 12: EmbodiedBench’s evaluation types.

Final Thoughts

VLA models represent significant progress towards more capable robotic systems, with companies beginning to heavily invest in developing larger and more capable models. However, the field remains in its infancy. Through researching VLAs for this piece, and my own interests, several questions have emerged that I would be excited to see more research on in the short to medium-term:

- What matters in Sim2Real for VLAs? While we understand that VLAs require fine-tuning for specific tasks, we need further insights into what causes failure when transitioning from simulation into the real world. Understanding these failure modes is essential for building robust VLA systems that can operate reliably in practice.

- How should VLAs compute? Should we optimise for edge deployment with smaller models running directly on robots, or leverage larger, more capable models running in data centers? This choice has important implications for model development and the design of robotic systems themselves.

- How do we handle VLA hallucination? LLMs have well-established methods for mitigating hallucination, but VLAs present unique challenges. When a robot hallucinates an action plan, the consequences are physical. How do we recover from bad plans or hallucination in VLAs? Can we do something similar to this?

- How do we achieve efficient data collection and curation for VLAs? Is it better to collect lots of examples of someone completing a task well or to just have a few very high-quality expert demonstrations of that particular task?

- How do we bridge RL and VLAs for continuous improvement? Traditional robotics has relied heavily on RL for policy optimization. How do we combine the strengths of both approaches? Can we use RL to fine-tune VLA policies for specific tasks while preserving their general capabilities? Or should we develop hybrid architectures where VLAs provide high-level planning while RL handles low-level control?

Citation

@article{quessy2025roboticlearning,

title = "Robotic Learning for Curious People",

author = "Quessy, Alexander",

journal = "aos55.github.io/deltaq",

year = "2025",

month = "July",

url = "https://aos55.github.io/deltaq/posts/an-overview-of-robotic-learning/"

}

References

T Brown, et al, Language Models are Few-Shot Learners, arXiv:2005.14165, 2020. ↩︎

OpenAI, Introducing ChatGPT, https://openai.com/index/chatgpt/, 2022. ↩︎

A Krizhevsky, I Sutskever, G E Hinton, ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, NIPS, 2012. ↩︎

Gemini Robotics Team, Gemini Robotics: Bringing AI into the Physical World, arXiv:2503.20020, 2025. ↩︎

N Lambert, J Morrison, V Pyatkin, S Huang, H Ivison, F Brahman, L J V. Miranda, et al, Tülu 3: Pushing Frontiers in Open Language Model Post-Training, arXiv:2411.15124, 2025. ↩︎

A Radford, et al, Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision, arXiv:2103.00020, 2021. ↩︎

Y Gong, YA Chung, J Glass, AST: Audio Spectrogram Transformer, arXiv:2104.01778, 2021. ↩︎

Q Wen, et al, Transformers in Time Series: A Survey, arXiv:2202.07125, 2023. ↩︎

J Xu, H Wu, J Wang, M Long, Anomaly Transformer: Time Series Anomaly Detection with Association Discrepancy, arXiv:2110.02642, 2022. ↩︎

L Chen, K Lu, et al, Decision Transformer: Reinforcement Learning via Sequence Modeling, arXiv:2106.01345, 2021. ↩︎

JB Alayrac, J Donahue, P Luc, A Miech, K Simonyan, et al, 🦩Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning, arXiv:2204.14198, 2022. ↩︎

H Touvron, T Lavril, G Izacard, E Grave, G Lample, et al, LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models, arXiv:2302.13971, 2023. ↩︎

OpenAI, GPT-4o System Card, arXiv:2410.21276, 2024. ↩︎

Gemini Team Google, Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models, arXiv:2312.11805, 2023. ↩︎

A Brohan, et al, RT-1 Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale, Robotics: Science and Systems, 2023. ↩︎

M O Torkoglu et al, FiLM-Ensemble: Probabilistic Deep Learning via Feature-wise Linear Modulation, arXiv:2206.00050, 2022. ↩︎

M Ryoo, AJ Piergiovanni, A Arnab, M Dehgani, A Angelova, TokenLearner: What Can 8 Learned Tokens Do for Images and Videos?, arXiv:2106.11297, 2022. ↩︎

Open X-Embodiment Collaboration, Open X-Embodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and RT-X Models, arXiv:2310.08864, 2023. ↩︎ ↩︎

B Zitkovich, et al, RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control, Proceedings of The 7th Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR 229:2165-2183, 2023. ↩︎

X Chen, et al, PaLI-X: On Scaling up a Multilingual Vision and Language Model, arXiv:2305.18565, 2023. ↩︎

D Driess, et al, PaLM-E: An Embodied Multimodal Language Model, arXiv:2303.03378v1, 2023. ↩︎

M Kim, K Pertsh, S Karamcheti, et al, OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model, 2024. ↩︎

S Karamcheti, S Nair, A Balakrishna, P Liang, T Kollar, D Sadigh, Prismatic VLMs: Investigating the Design Space of Visually-Conditioned Language Models, Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning 2024. ↩︎

H Touvron, T Scialom, et al, Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models, arXiv:2307.09288, 2023. ↩︎

X Zhai, B Mustafa, A Kolesinov, L Beyer, Sigmoid Loss for Language Image Pre-Training, arXiv:2303.15343v4, 2023. ↩︎

M Oquab, T Darcet, T Moutakanni, H Vo, M Szafraniec, V Khalidov, P Labatut, A Joulin, P Bojanowski, et al, DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision, arXiv:2304.07193, 2024. ↩︎

E Hu, Y Shen, et al, LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models, arXiv:2106.09685, 2021. ↩︎

Y Wang, H Zhu, M Liu, J Yang, HS Fang, T He, VQ-VLA: Improving Vision-Language-Action Models via Scaling Vector-Quantized Action Tokenizers, arXiv:2507.01016, 2025. ↩︎

K Black, et al, $\pi_{0}$: A Vision-Language-Action Flow Model for General Robot Control ↩︎

Y Limpan, R Chen, H Ben-Hamu, M Nickel, M Lee, Flow Matching for Generative Modelling, arXiv:2210.02747, 2022. ↩︎

L Beyer, A Steiner, A Pinto, A Kolesnikov, X Wang, X Zhai, et al, PaliGemma: A versatile 3B VLM for transfer, arXiv:2407.07726, 2024. ↩︎

Q Li, Y Liang, Z Wang, et al, CogAct: A Foundational Vision-Language-Action Model for Synergizing Cognition and Action in Robotic Manipulation, arXiv:2411.19650, 2024. ↩︎

J Wen, et al, TinyVLA: Towards Fast, Data-Efficient Vision-Language-Action Models for Robotic Manipulation, arXiv:2409.12514, 2025. ↩︎

M Shukor, D Aubakirova, F Capuano, et al. SmolVLA: A vision-language-action model for affordable and efficient robotics, arXiv:2506.01844, 2025. ↩︎

Team AgiBot-World, AgiBot World Colosseo: A Large-scale Manipulation Platform for Scalable and Intelligent Embodied Systems, arXiv:2503.06669, 2025. ↩︎

NVIDIA, GR00T N1: An Open Foundation Model for Generalist Humanoid Robots, arXiv:2503.14734, 2025. ↩︎

V Dean, Y G Shavit, A Gupta, Robots on Demand: A Democratized Robotics Research Cloud, Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Robot Learning, PMLR 164:1769-1775, 2022. ↩︎

D Pickem, P Glotfelter, L Wang, M Mote, A Ames, E Feron, M Egerstedt, The Robotarium: A remotely accessible swarm robotics research testbed, International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2017. ↩︎

N Gürtler, et al, Real Robot Challenge 2022: Learning Dexterous Manipulation from Offline Data in the Real World, Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2022 Competitions Track, 2022. ↩︎

Z Wang, Z Zhou, J Song, Y Huang, Z Shu, L Ma, VLATest: Testing and Evaluating Vision-Language-Action Models for Robotic Manipulation, Proceedings of the ACM on Software Engineering, 2025. ↩︎

B Zhang, Y Zhang, J Ji, Y Lei, J Dai, Y Chen, Y Yang, SafeVLA: Towards Safety Alignment of Vision-Language-Action Model via Safe Reinforcement Learning, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2025. ↩︎

Physical Intelligence, $\pi_{0.5}$ a Vision-Language-Action Model with Open-World Generalization, 2025. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

E K Jones, et al, Adversarial Attacks on Robotic Vision-Language-Action Models, arXiv, 2025. ↩︎

H Cheng, E Xiao, et al, Manipulation Facing Threats: Evaluating Physical Vulnerabilities in End-to-End Vision Language Action Models, arXiv:2409:13174, 2024. ↩︎

J Wei, X Wang, D Shuurmans, M Bosma, B Ichter, F Xia, E H Chi, Q V Le, D Zhou, Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models, arXiv:2201.11903v6, 2023. ↩︎

S Zhang, Z Xu, P Liu, X Yi, X Qiu, et al. VLABench: A Large-Scale Benchmark for Language-Conditioned Robotics Manipulation with Long-Horizon Reasoning Tasks, arXiv:2412.18194, 2024. ↩︎

O Mees, L Hermann, E Rosete-Beas, W Burgard, CALVIN: A Benchmark for Language-Conditioned Policy Learning for Long-Horizon Robot Manipulation Tasks, arXiv:2112.03227v4, 2022. ↩︎

R Yang, H Chen, J Zhang, M Zhao, et al, EmbodiedBench: Comprehensive Benchmarking Multi-modal Large Language Models for Vision-Driven Embodied Agents, Proceedings of the 42 nd International Conference on Machine Learning, 2025. ↩︎